Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorPosts

-

Hi Jack,

The language of the 75-Pfennig note is not only Low German but a medieval form of it; it translates as “Johann noble lord of Diepholz gave the citizens of Diepholz their town charter in the Year of God’s birth (sic) 1380”. The theology of this claim is fractionally dodgy as the year is 1380 after Christ’s birth, but hey …

The gentleman in question is Johann III of Diepholz, ruled 1378-1422. The line died out in 1585.

The reverse of 50-Pfennig note #1 (Lemförde) is in more modern Low German and reads : Wo et so vele Lumpen gift / Von Dag hier up de Welt / Is et keen Wunner dat man blot / Ut Lumpen makt dat Geld. / Ward doch so männig Lump verehrt / De keenen Pennig gelt an Wert.

One translation would be : “As there are so many ragged scraps / Around these days in the world / Then it’s no wonder that one just / Uses rags to make the money. / There’s many a raggedy scrap held in great esteem / Which isn’t worth a penny.”

On one level this seems to be bemoaning the worthlessness of paper money. Paper was often made from rags; I’ve just reminded myself how this was done with processes involving drums with revolving spikes called “devils”, caustic soda, lime, “breaking engines”, bleaching agents, “potching engines”, “half stuff”, “beating engines” etc. I seem to remember having this explained to me at an olde worlde paper mill about 45 years ago and my brain went as numb then as it does now..

Anyway, the word Lumpen (plural) has a double meaning in German; it can mean rogues or scoundrels or rascals or rapscallions (you get the idea), so the hidden meaning of the poem is : “There are so many scoundrels around in the world, …. There’s many a scoundrel held in great esteem / Who isn’t worth a penny.”

Sadly, English hasn’t got the same pair of homonyms so it’s difficult to bring out the double meaning in a single translation.

The 75-Pfennig note # 1 (Church) is also in more modern Low German. It translates as : “History tells us of the people of the parish that they have their own gallows and execution wheel, and a court that sits between the moor and the heathland, and that they eat buck wheat blossom honey and rye gruel. Long ago it was different, we used to have it so good, now everything is scarce again, even the rye for the bread.”

The word in inverted commas in the text, “Kaspeler” (with an additional -e for the dative plural), is a specifically local word for those who attend the church as part of the parish, the Kirchspiel, which Low German dialect renders here as Kaspel, hence Kaspeler = “parishioners. Thanks to Dr Ulrich Müller for his piece on the church at Barnstorf and this little gem of linguistic information.

I’ve translated the word Rad by way of explanation as “execution wheel” rather than just “wheel”, as this is one of the three examples of Diepholz having a measure of judicial independence, the other two being the self-explanatory gallows and court, i.e. they could try people and exact fines and impose punishments, including the death penalty. “Breaking on the wheel” was a particularly ghastly form of execution practised across Germany (although I’ve heard of at least one case in 17th-century France), details of which I don’t think I shall bother forum frequenters with here. If people are interested they can look it up, preferably not after having eaten.

I advise that especially because the 75-Pfennig note with the goose and the pig concerns their relative merits as food rather than cuddly farmyard friends. The Low German translates as :

“Goose breast is a thing we smoke, / Everyone knows that to be a fine dish, / And also a juicy slice of roast pork / Is nice when it turns out well. / And so we want at all times / To engage enthusiastically /In goose and pig husbandry.”

Hope that this is of use and interest!

Best wishes as always :)

Greetings John et all;

Once again, a very informative response by John.

Today we look at Diepholz.

75 pfg in series 272.1 involves somebody named Johann and a place named Diepholz. The rest may be in German. But it is another dialect of it… I think.

In fact, I think this dialect, if that is the cause, may well be the issue with 272.3

Thanks,

Jack

<><><><><>

75 pfg, Johann in 1380, 18 July 1921

Writing on the front:

Johann edele here tho Depholt hedde den Borgern tho Depholt de stades recht gegenen na Gades gebort A. 1380.

(translated 13 November 2020)

Johann edele here tho Depholt hedde the Borgern tho Depholt de stades right against na Gades born A. 1380

<<???>>

SERIES 273.3:

50 pfg, Lemforde, 15 Aug 1921, # 1420

Writing on the front:

Wo et so vele Lumpen gifft

Bondag heir up de Welt

Is et keen Wunner dat man Blot

Ut Lumpen Makt dat Geld

Ward doch so manning Lump verehrt

De keenen Penning gelt an Wert

(translated 20 November 2020)

Where there are so many rags

Bondag heir up the world

Is et keen Wunner dat one blot

Ut rags Makt dat money

Was such a manning scoundrel worshiped

De keenen penning is valued

<<???>>

75 pfg, Kirche, 15 Aug 1921, # 4557

Writing on the Front:

Von den Kaspelern vermelet de Geschicht

Se harrn en eegen Galgen Rad un Gericht

Dat se binnen Moor un Heidentum heft seeten

Bokweetenjanhinnerk un Rogenbree eeten

All langst wor dat anners et gung us so good

Nu is alls weddr Knapp ok de Roggen ton brod

(translated 25 November 2020)

The story is told by the Kaspelern

They have their own gallows wheel in court

That they lived within Moor and Heidentum

Eat buckwheat and rye bread

All long was that otherwise it went so well for us

Now all weddr Knapp is ok the Rye tons of bread

<<???>>

75 pfg, Bauer mit Schwein und Gans, 15 Aug 1921, # 18354

Writing on the front:

Gerökert is de Gosebost

jeder ‚weet ‘ne leckre Kost

Un ak en saft’ge Sweinebraen

Is moje wenn he god geraen

Us op de Gos=un Sweintucht smieten

(translated 26 November2020)

Gerökert is de Gosebost

As everyone knows some delicious food

Un ak en juicy Sweinebraen

Is moje when he god got it

Us op de Gos = to rent a swine towel

<<???>>

Text by: J H Wordermann <?>

Hi Jack,

The Dessau set is one of my favourites! The notes recall episodes and stories from the life of Leopold I, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau (1676-1747), known affectionately as der alte Dessauer (the Old Dessauer). Considered a military genius, he is credited with inventing marching in time to speed up the movement of infantry formations, and the invention of the metal ramrod. He perfected infantry drill and was known as the “drillmaster of the Prussian army”. A real character, the prince was given a starring role in a volume of humorous anecdotes by the popular author Karl May.

Note 1 : The slow infantry march, the Dessauer March or simply “the Old Dessauer”, was first played after the Battle of Cassano on 16th August 1705.

– Note 2 : Upon his accession, Prince Leopold married his childhood sweetheart, the court apothecary’s daughter Anna Luise Föhse.

– Note 3 : At the First Battle of Höchstedt (or Höchstädt) on 20th September 1703, Prince Leopold saved the Imperial army from utter destruction by his spirited rearguard action against the French and Bavarians.

– Note 4 : The Second Silesian War (1744-45) was part of the War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) and confirmed Prussian control of the Austrian province of Silesia.

– Note 5 : In the Battle of Kesselsdorf on 15th December 1745, the Prussians under Prince Leopold defeated the joint Saxon and Imperial army under Field Marshal Rutowsky. The quotation in Note 4 and the prayer in Note 5 are both supposed to have been uttered by the Old Dessauer before this battle.

– Note 6 : According to local legend, the prince once asked some market traders in pottery how profitable their day had been. When they lamented a bad day’s trading, Leopold drove his horse repeatedly through their wares and then told them to go up to the palace where they would be compensated for the breakages, thus ensuring that they turned a good profit.

Hope this helps! Best wishes as always

‘REVALUED GEMS (Volume 1)’ has just been published for anyone who is interested. John and Marcel helped me get this project off the ground and to its completion. It contains ALL the revalued / overprinted serienscheine pieces AND other grossgeld and inflationary notgeld pieces A – K.

I hope the collectors like it.

Ello all,

Today we look at Dessau. It tells a tale across several notes. I am wondering if anybody can offer the full tale by note.

Translations are not an issue today. Understanding the context is.

Thanks for all the help you can offer.

I have placed here the interesting story of the windmill shown on the Daler notes.

Old Bockmolle

The windmill at Dybbol is not just a building that has been existent in some form for several centuries. It has been a souce of pride. Both in how it supported the locals militarily, and in supporting the locals in a culinary rebellion. The cakes this windmill helped to produce would become a tradition of rebel cakes in southern Jutland.

Records have a windmill at this site grinding wheat into flour as early as 1774. It has been battled by wars and burnt at least twice. The rebel cakes came about because in 1864 combined forces of the Kingdom of Germany and the Austro Hungarian Empire occupying Southern Jutland. For whatever reason, the occupying forces would not permit the community centers the locals used to have alcohol licenses. So cakes went from side items to the centerpieces. To further the point of not giving up any more than they had to, they used the flour from the local mill. They were going to stay as unchanged as much as they could.

Flour and food aside, the windmill at Dybbol had a more memorable impact on Danish history. To start with, there was a second Schleswig war in 1864. And windmills were among the tallest of buildings in rural environments. So it makes sense for the Danish forces to use the high vantage point for military purposes. In 1864 the was as an observation post, sending signals to the troops in battle. Sadly, for the Danish Army, the Prussian – Austrian army was better prepared. Victory went to the invaders and along with it went Southern Jutland.

It would burn to ruin during the year 1913.

Thanks, John, your help is full of wisdom as usual.

Hi Jack,

it’s actually the Dead Maar rather than the Dead Sea (Totes Meer), a maar being a low-lying volcanic crater usually filled with a lake. The maar in question is actually the Weinfeld Maar in the volcanic Eifel region, made famous by the slightly obsessive artist Fritz von Wille, who painted it repeatedly with the small chapel of St Martin on the north bank, as seen on the note. The cemetery surrounding the chapel is still in use, which is where the maar gets its other name, the Totenmaar or Maar of the Dead. The note renders the name as the Dead Maar : Am Toten Maar, which is grammatically incorrect.

The Latin Eifliam nescit qui Dunam ignorat means : “He does not know the Eifel who does not know Daun”.

Best wishes as always,

John

Ello all.

Today we look at Daun. The dead sea line does translate word wise. Yet I would have to wonder why the locals would want to advertise a dead sea. Or at least using that name. this is a filled volcano who waters are not at all dead. A biblical reference I am not realizing? Or just honoring the sea or lake in a dead volcano.

50 pfennig, Am Toten Maar, 20 Feb 1920, #026223

Writing on the front:

Am Toten meer bei Daun

(translated 6 March 2014)

At the Dead Sea near Daun

Eifliam nescit qui dunam ignorat

(translated 18 March 2014)

Eifliam not know who does not know Daun.

<<???>>

Thanks,

Jack

Hi Jack,

The Dalhausen text, taken from a plaque recording the founding of Our Lady’s Church in Dalhausen, a site of local pilgrimage, is indeed in Latin, although less of a Latin than Julius Caesar would have recognised. It’s not Classical Latin but post-Medieval Latin, Church Latin and a bit of German-inflected Greek thrown in.

There’s also an error in transcription, with unhelpful commas added mid-word; as is not unusual with Latin on monuments, it also has words running directly from one line into the next, and some words running directly into others without spacing, and some words abbreviated. So what you can read is this :

IN HONOREM MAGNÆ / MATRIS VIRGINIS / IMMACULATÆ ECCLE / SIA HÆCEX FUNDA, /MENTO ÆDIFICATA / SUMPTIBUS PRÆNOBI, / LIS ASCETEREY GERDEN / SIS SUBRMA ACPRAENO, / BILI DÑA VICTORIA DORO, / THEADEIUDEN ABBATISSA

But when one tidies up the Latin, you get this :

IN HONOREM MAGNÆ MATRIS VIRGINIS IMMACULATÆ ECCLESIA HÆCEX FUNDAMENTO ÆDIFICATA SUMPTIBUS PRÆNOBILIS ASCETEREY GERDENSIS SUB R[O]MA AC PRAENOBILI DÑA VICTORIA DOROTHEA DE IUDEN ABBATISSA

Which translates in to English as this :

“In honour of the Great and Immaculate Virgin Mother this building was erected at the expense of the noble abbey of Gehrden under [the Holy See of] Rome and the noble Lady Victoria Dorothea von Juden, [its] abbess.

Hope this helps!

Best wishes as always,

John

Ello all,

Today we look at Dalhausen in Westphalia. Some of the text seems to be in Latin, though the conjoined AE characters may be throwing things off. Latin mixed with another dialect perhaps?

<><><><><><><><><>

<below is Latin>

In Honorem Magnae,

Matris Virginis

Immaculate Eccle

Sia Haecex Funda

Mento Aedificata

Sumptibus Praenobi

Lis Ascetery Gerden,

Sis SubRma AcPraeno,

Bili Dna, Victoria Doro

Theade Iuden Abbatissa

Anno 1718

(translated 24 October 2020)

To the greater honor of

Virgin Mother

immaculata Church

Established Sheva Haecex

The rib chin

Ex Praenobi

Us Ascetery Gerden,

Please SubRma AcPraeno;

Bili DNA, Victoria Dorus

Thead iudcum Abbatissa

in the year 1718

<???>

Thanks,

Jack

Great knowledge swapping and sharing – thanks everyone!!

Hi Jack,

regarding the Daler set, I think your translations from the Danish are pretty spot on. In my own translations for my collection, I had the couplet on the reverse of the notes as “We have long had such a longing and yearning / This year we will farm with gladness and song”. The word avler does mean “breed” but it also means “cultivate” so I assumed that the rural inhabitants of the small parish of Daler were looking forward to going about their agricultural work with greater joy, now that they had the prospect of being restored to Denmark, having been annexed by Prussia in 1867.

You’re absolutely right about the reference to the plebiscite. The first North Schleswig Plebiscite, for Zone I, took place on 10th February 1920 (hence the Vort Ønske er opfyldt den 10. Februar 1920 : “Our wish was fulfilled on the 10th February 1920”. The notes were issued on 10th April, so after the votes had been counted and verified by the Treaty Commission and the result of the plebiscite had been announced, but before the transfer of power which was to take place on 15th June – which is why the notes were issued in Pfennigs rather than Øre, as Daler still had another couple of months belonging to Germany.

Best wishes as always,

John

Ello all,

Today we have Daler. The system seems to think the text is in Danish. However, some of the translations seem a bit off. Also there may be some cultural references I am missing.

25 pfg, Windmill, 10 Apr 1920, # 42761

Writing on the front:

Den gamle Bockmolle i Daler

Bygget 1770 Nedbrændt 1913

<above is Danish>

(translated 27 September, 2014)

The old Bockmolle in Daler

Built 1770 Burnt down 1913

Vi har saa ofte saa et i Længsel og Trang

I dette Aar avler vi med Glade og Sang

<above is Danish>

(translated 27 September, 2014)

We so often have one in longing and longing

This year we breed with joy and song

<<breed???>>

Writing on the back:

Vort Onske er opfyldt

Den 10 Februar 1920

<above is Danish>

(translated 27 September, 2014)

Our request is fulfilled

The February 10, 1920

>>>does this refer to the Danes wining the plebiscite?

Thanks again,

Jack

But what about the poor servant who had to get the donkey back down???

It is reasonably certain the donkey did not want to go up those stairs in the first place.

lol

Hi Jack,

The Coblenz- Neuendorf series is an interesting one, issued against the background of the intended French destruction of the fortress town Koblenz’s system of forts (in the event, only the Feste Kaiser Alexander and small parts of the Fort Großfürst Konstantin were destroyed, and Ehrenbreitstein was entirely spared). The reverse of the 50-Pfennig note commemorates the glorious dead of the recent Great War with a cenotaph decorated with oak leaves, a Stahlhelm and a bayonet, declaring the town to be Loyal to [the memory of] the Dead (Treu den Toten). It centres on a mash-up of lines 5-12 of verse 10 of Schiller’s 1803 poem Das Siegesfest (The Victory Festival) which celebrates the fallen heroes of the Trojan War.

The original is : Der für seine Hausaltäre / Kämpfend ein Beschützer fiel – / Krönt den Sieger größre Ehre, / Ehret ihn das schönre Ziel! / Der für seine Hausaltäre / Kämpfend sank, ein Schirm und Hort, / Auch in Feindes Munde fort / Lebt ihm seines Namens Ehre (He who fell as a protector / Fighting for his house’s altars – / Greater honour crowns the victor, / And honours him the finer goal! / He who collapsed as defender and treasure / Fighting for his house’s altars, / The honour of his name lives on / Even in the mouths of his enemies).

The note has it thus : Wer für seine Hausaltäre / Kämpfend ein Beschirmer fiel – / Krönt den Sieger größ‘re Ehre, / Ehret ihn das schön‘re Ziel! (Whosoever fell as a defender / Fighting for his house’s altars – / Greater honour crowns the victor, / And honours him the finer goal!)

On the front it has the terms of validity : Dieser Gutschein verliert seine Gültigkeit 3 Monate nach Ausstellung (This note loses its validity three months after the date issued). The word Ausstellung can mean “exhibition” – and there are notes issued on the occasion of Notgeld exhibitions e.g. at Kahla – but it can also mean “issuing”.

The reverse of the 75-Pfennig note depicts a well-known address in the Koblenz suburb of Neuendorf, namely Am Ufer 11 (Number 11, On the Riverbank), otherwise known as Das Haus der Nell (The House of the Nell Family). It has a historic archway (Historisches Tor), depicted here, with an ancient inscription, which can still be seen today : DIESES HAUS UND HOFE SIND FREIJ, WER ES NICHT GLABEN WIL, DER LECC MICH IM ARSCH UND GEHE VORBEIJ (“This house and courtyard are free, whoever doesn’t believe it can kiss my arse and pass on by”). “Free” in this sense means owned by a free family of proud lineage; the vulgarism literally invites the unbeliever to “lick me in the arse”, which as a phrase has a certain pedigree in German (it’s what the knight Götz von Berlichingen famously invited the Emperor to do back in the 16th century).

The picture shows a particular scion of the Nell family, either Major Peter von Nell or Major Christian von Nell, or at any rate the presumed builder of the house in the early 18th century. The verse claims him to be an amusing man, no doubt because of the inscription he had placed above the archway : EIN LUSTIGER GESELL, / DAS WAR DER MAJOR NELL, / BIS AUF DEN SÖLLER RITT ER JUST / MIT SEINEM ESEL VOLLER LUST, / DOCH SEINEN BÖSEN NACHBARN SCHIER / VEREHRT ER DIESE INSCHRIFT HIER (“A droll fellow / Was Major Nell, / He rode upon his donkey full of spirit / All the way up to his attic room, / But with this inscription here / He honours his awful neighbours). In other words, the inscription is an amusing and vulgar way of warning away trespassers who might enter into his courtyard.

Well might he issue the warning! These days Neuendorf has a bit of a reputation as a problem neighbourhood, a sozialer Brennpunkt as the Germans say. Only last Christmas the denizens of this troubled area on the north of the Moselle and the west of the Rhine, just above where the rivers meet at the Deutsches Eck, were shooting fireworks at the police. It’s an area beset by gang culture and drugs.

By the way, like most German towns formerly beginning with the letter C (e.g. Crefeld, Cranichfeld, Cüstrin), Coblenz swapped its initial letter to a K and became Koblenz during the Weimar period (in this case, on 14th May 1926).

Hope this is all of interest! Apart perhaps from the suburb of Neuendorf, Koblenz is definitely worth a visit; although I was once troubled in the toilet at McDonald’s there back in 1988 by an unreconstructed type (possibly from Neuendorf), I’ve enjoyed the town a number of times, especially for the “Rhine in Flames” in the summer when boats on the river provide a mobile firework show which is legal, above board and not aimed at the forces of law and order. Rather unfortunately, the last time I was there I woke up to the realisation that I had caught Covid! Oops.

<><><><><><><><><><><><><><>

Ello all,

Today we look at Coblenz Neuendorf. It seems to be another series that honors the dead. Sadly for those who survived, the Great War would have produced a lot of inspiration for war related notes. Notes that as often as not would bring to mind the lost.

50 Pfennig, 01 October 1921, war memorial?

Writing on the front:

1914 Treu den Toten 1918

(translated 29 March, 2016)

1914 Trust the Dead 1918

<or>

1914 the Faithful Dead 1918

(As I have said, my project is to find the message in the money for the person holding the note. I can see a message being sent with either. I suspect it is the second, but not absolutely sure)

Wer für seine hausaltäre kämpfend, ein beschirmer, fielkrönt den sieger gröss’re ehre, ehret ihn das schön’re ziel!

(translated 29 March, 2016)

Who fight for his house altars, a protector of, was crowned the winner gröss’re honor, it honors the schön’re goal!

<???>

Writing on the back:

Dieser gutschein verliert seine Gültigkeit 3 monate nach ausstellung

(translated 29 March, 2016)

This voucher is valid until replaced 3 months after exhibition

<???>

(another new term to my work. Was this sold/circulating at an exhibition of some kind?)

75 Pfennig, 01 October 1921, historic gate?

Writing on the front:

Nachbarn schier verehrt er diese inschrift hier, ein lust iger gesall das war das major nell, bis auf den söller ritt er just mit seinem esel voller lust, doch seinenbösen.

(translated 29 March, 2016)

Neighbors seemingly he worshiped this inscription here, a funny gesall that was the major nell until the upper chamber he rode just with his ass full of lust, but his evil.

<???>

Dieses Haus und Hofe ist Frei

Wer es nicht glaben wilder lecc nich am aschvnd gehevodrbejj

(translated 29 March, 2016)

This house and Hope is free

Those who do not believe it wild LECC nich gehevodrbejj on aschvnd

<???>

<also not sure I read the text over the arch correctly>

Thanks,

Jack

Thanks John.

Tony… Oh, it is. the only way to move any faster is to give up trying to translate the notes myself and just send the text stright to him.

lol

forgive me if I still try to put some effort into it. :)

Thanks John!

Jack – I hope your project is really progressing well now with John’s expert input.

Hi Jack,

The six notes tell the story of how the wooden statue of the town’s Roland (see also my earlier post on the Bad Bramstedt notes) was carved in 1656-1658 by the master wood carver of Magdeburg, Gottfried Gigas. It was, sadly, burned by the townspeople for fuel during the harsh post-war winter of 1946-1947.

In 1976 a sandstone version, based on pictures of its predecessor, replaced the lost Roland. It has the foreshortened and disproportionate arms of the 17th-century version.

Here’s are the original texts and translations.

Picture 1

Zu drein schritt würdig durch das Tor / Der hochwohlweise Rat hervor.

The council of the town, most wise / As a trio stepped worthily through the gate /

Picture 2

Gemächlich ging er aus zum Wald / Und fand dort eine Eiche bald.

Nun höre, Meister Holzstecher – Daraus mach‘ einen Roland Er!

Leisurely the went out to the woods / And soon found an oak tree there.

Now listen, Master Woodcutter – / Make from it a statue off Roland!

Picture 3

Mit Messer, Stichel, Stift und Schlag / Trat Kopf Leib und Fuß zutag.

Doch für die Arme – mögt verzeihn / Ihr Herren! – ist dieser Stamm zu klein

With knife, chisel, bradawl and hammer / The head and body and feet appeared.

But for the arms – forgive me, / My lords! – this tree trunk is too small

Picture 4

Sie schritten wieder hin zum Wald / Und fanden auch das Stämmchen bald.

Nun höre, Meister Holzstecher – / Daraus mach‘ nun die Arme Er!

They stepped out to the woods once more / And found the little tree trunk soon.

Now listen, Master Woodcutter – / Make from it now the arms!

Picture 5

Ein Schmäuschen gab die Stadt zum Lohn / Doch Roland fehlt – die Proportion!

The town gave a small banquet as a reward / But Roland lacks – proportion!

Picture 6

Wohl hält er treulich seine Wacht, / Nur weint vor Scham er, kommt die Nacht.

Loyal and well he keeps his watch, / But he weeps for shame, when night falls.

The last picture of the poor disproportionate Roland with his little arms, coming to life at night, turning his back in shame and weeping into his hands as the moon looks on, is quite touching in a Toy-Story kind of way. You can find a picture of Calbe’s Roland at

http://www.calbe.de/tourismus-kultur/sehenswertes/der-roland/index.html.

Hope that this is helpful.

Best wishes as always.

Thank you.

Any source that has the complete text/ translation of these Caabe notes?

It is interesting. As much as these are for collectors, it would shock me greatly if nobody tried to use them as currency. As I understand it, the value of the national currency was dropping quicker than gravity, and notgeld was based on hard currency or asset the issuer had access to. Then again, a one day fair was a good as any to limit their exposure to any collectors who would not want to lose them. A guaranteed fundraiser for those that issued them.

Hi Jack! – I was just thinking out allowed here really – some of the notes that were issued for collector exhibitions would have only been valid for 1 or 2 days……but good little observation with the Calbe notes!

Ello all,

The information, as always has been useful. Today we look at Calbe an der Saale.

This series appears to literally tell a story. Possibly something about a Roland statue? Currently I only have two of the notes scanned but prob have more in a few albums I have set a side while I do the first group.

Incidentally, this is the first series I have encountered that seems to be good for one day only.

<><><><><><><><>

50 pfg, Bild 2, Group and Woodcutter, 23 Apr 1917, # 81954

Duplicate: # 87215

Writing on the front:

Stadt Calue a.d. Saale

(translated 07 October 2020)

Calbe an der Saale

<Calue is an older word for ‘woods’?>

>>so ‘woods on the Saale… effectively it seems they named the place ‘

Gemächlich Ginger aus zum Wald

Und fand dort eine Eiche bald

Nun höre Meister Holzstecher

Durans mach einen Roland Er!

(translated 07 October 2020)

Leisurely Ginger out to the forest

And soon found an oak tree there

Now listen to Master Holzstecher

Durans make a Roland He!

<<???>>

(possibility that ‘Ginger’, ‘Holztecher’ and ‘Durans’ are names with the idea this is an image of them instructing the woodsman/artist to make a Roland statue?)

<><><><><><>

50 pfg bild 6, ?????, 23 Apr 1917, # 162786

Writing on the front:

Wohl halt treulich seine Wacht,

Nur weint vor Scham er, kommt die Nacht

(translated 09 October

Keep his watch faithfully,

Only he cries in shame, the night comes

>>>translation of words, ok. Seeming to make sense, not so much

Thanks,

Jack

Hi Jack,

Regarding the 25-Pfennig Butzbach note, yes it is indeed in a dialect of German, this time Hessisch (in English, Hessian), as Butzbach is about 15 miles north of Frankfurt in the Federal State of Hessen.

The picture shows locals in their traditonal dress, worn on high days and holidays and special occasions. Such Trachtenfeste (festivals in traditional local costume) are a major draw for outsiders; we as a family go to a couple of them every summer in Bavaria. Down there it’s lots of leather trousers, dirndls and hats with goats’ beards, although some villages have Tracht not dissimilar to that shown here, with tricorns and frock coats and bolero jackets and pillbox hats. So the people looking out of the note at the beholder are issuing an invitation : Wollt’r üüs leawig sih, / Müsst’r uff Boutschbach gih (“If you want to see us in real life, / Then you have to go to Butzbach”).

Hope this is of interest and assistance! Best wishes as always.

Hi David!

I have now got hold of a copy and am about half way through it. Yes, quite hard going in places but very good ofr understanding of the time and situation and the causes of all the monetary problems, including of course the hyper-inflation.

Greetings all.

Today have the joy of thinking about Butzbach., specifically series 212.1a.

I am guessing this is yet another Dialect that is somehow German in its way?

25 pfg, peasants, # 60573, 06 May 1921

Writing on the front:

Wall’r uus leawig sih Musst‘r uff Boutschbach gih

(translated 29 September 2020)

Wall’r uus leawig sih Mustst‘r uff Boutschbach gih

<<???>>

Thoughts on the front image:

<<Groups of people looking out from the notgeld note as if they were ‘breaking the fourth wall’>>

Thanks again,

Jack

Hi Jack,

the quotations you’re looking at on the Bützow notes are in the Mecklenburger Platt dialect and come from one of Fritz Reuter’s works, Ut mine Festungstid (“My Time in Prison”), where the authors narrates amusing autobiographical episodes from his years imprisoned in a Prussian fortress as a political undesirable.

On the 25 Pfennig : Wat nützt uns de Leiw’, wenn de Nohrung fehlt (What use is love, when we don’t have food) comes from Chapter 24 of the book.

On the 50 Pfennig note : Uns’ Herrgott helpt blot den, de sick sülwen helpt! (The Lord our God helps only him who helps himself!) is from Chapter 12.

There is a useful book on the Reutergeld, but it’s in German : Das mecklenburgische Reutergeld von 1921 by Ingrid Möller. It’s also available as an e-book on Amazon Kindle.

Best wishes as always,

John

Greetings,

Thanks John, that was quite an interesting view into the legal systems of Brauchhausen during those times. Troubling as the justice system may seem to defendants these days, this shows that it was worse before.

Today we review series 205.1 in Butzow. It is a reutergeld series. One of these I am going to try to buy a set of all the reutegeld town issues. I have to wonder if there is a dedicated book written by and or for reutergeld collectors that covers what quotes the issuer was looking at.

Thanks all,

Jack

<><><><><><><>

25 pfg, Fruit farmer, 28 Feb, 1922

Writing on the back:

Mat nutzt uns de Leiw‘ wenn de Nohrung Fehlt

(translated 26 September, 2020)

Mat is useful to us when there is no learning

<<???>>

50 pfg, Townscape, 28 Feb, 1922

Writing on the back:

Uns Herrgott helpt blot den die sick sülwen helpt

(translated 26 September, 2020)

Lord God help blot that sick sülwen helps

<<???>>

Hi Jack,

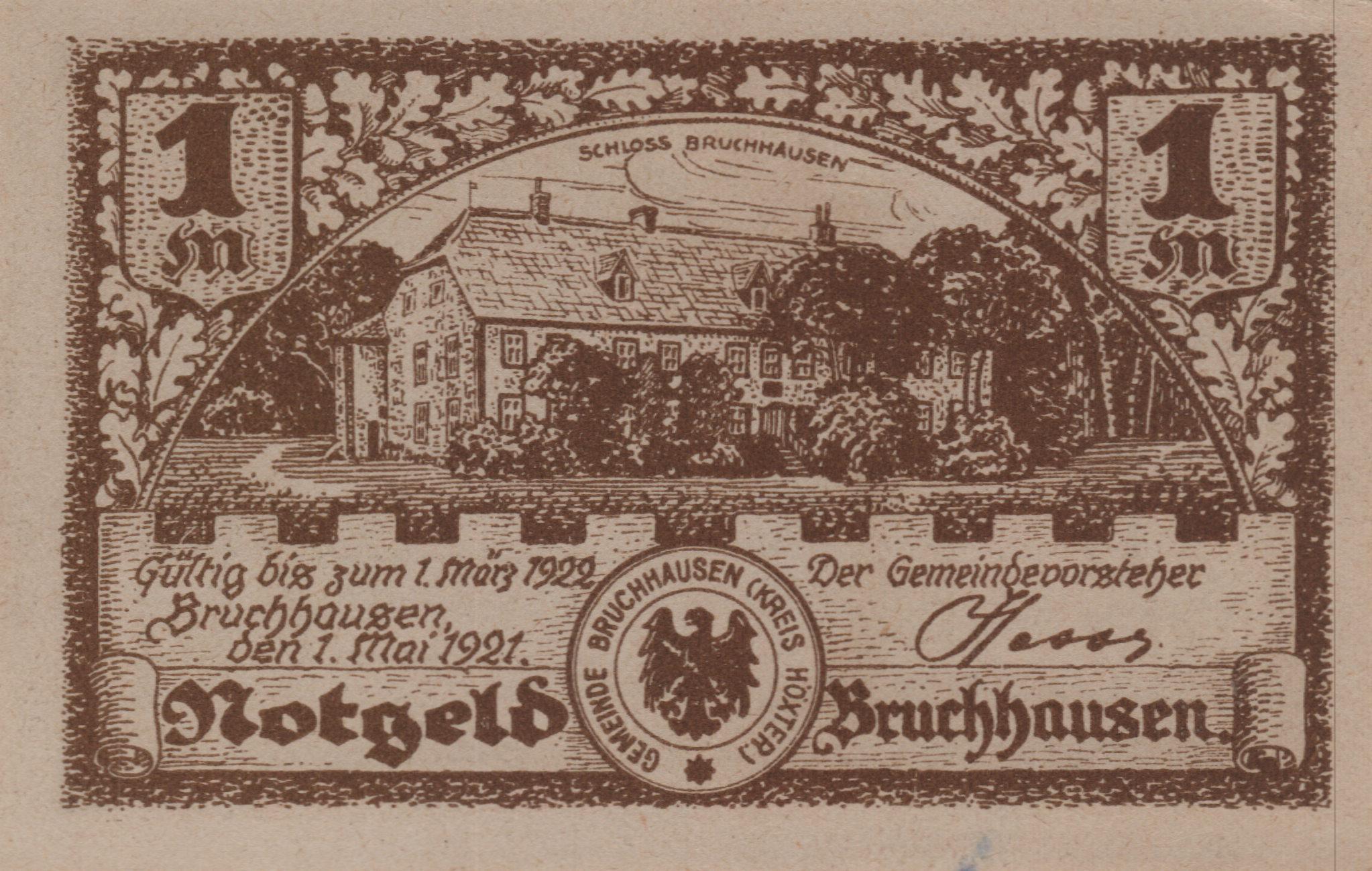

the Bruchhausen notes depicts a court scene of the day of the Heilige Fehme, not the Holy Woman but the Sacred Fehme Court of Bruchhausen; the Fehme or Vehme courts were secret courts or tribunals which were active, principally in Westphalia, during the Middle Ages, although they continued to exist until the introduction of the Napoleonic Code in the first years of the 19th century. Here are my notes on the scene :

Against a background of oakleaves, that very German of symbols, a handbill appears to be nailed, in the fashion of the summons to the Fehme court which the accused would find affixed to his door in the dead of night. Upon it, a short sword is stylised to form the figure 1, and pieces of rope to form the word Mark. The main image shows a table beneath an oak tree from which a noose is already suspended, the means by which the guilty would be punished, left hanging in a public place as a warning; on the table is a sword, symbolising the right of the court to issue sentences of death. Also on the table is a book, most likely a bible to administer oaths, and a cross which lends the table the appearance of an altar. The whole scene takes place in a town square, which is perhaps surprisingly public for a supposedly secret court; the Fehme courts are popularly believed to have been convened at night time.

In this case, the secrecy is maintained by the judges wearing black gowns and black hoods; the figure on the left is seen side on, and we can see that the hood stretches all the way down his back. Traditionally there were, as here, seven lay judges or Freischöffen, the leader of whom was known as the chairman or Stuhlherr. The eighth man in black, taller, muscular, dressed in figure-hugging doublet, breeches and hose, and standing menacingly behind the bound prisoner, is surely the executioner.

A picture from the 1375 Herforder Rechtsbuch (“Book of Law” of Herford, also in Westphalia) shows a Fehme court in session, with features recognisable on the notes – the sword on the table, the reliquary with a cross on top for administering oaths, even the long hoods of the lay judges. The secrecy of the gathering does not appear to be of paramount importance here, perhaps because it is a closed session.

In the 1920s, murders of political opponents by the Far Right, particularly by the secret Organisation Consul and its successors, were called Fehmemorde (Fehme murders) after the whistle-blowing article and follow-up book (Verschwörer und Fehmemörder – Conspirators and Fehme Murderers) of former member Carl Mertens in 1925. These included the murders of the head of the Bavarian Socialist republic Kurt Eisner in 1919, of the Communist politician Karl Gareis and the Armistice signatory Matthias Erzberger in 1921, and of Foreign Minister Walter Rathenau in 1922. Is it perhaps a striking coincidence that the issue of these notes in May of 1921 was followed by the murder of Gareis in June and Erzberger in August?

Hope this is helpful to you and of interest to GNCC members!

Best wishes as always!

Correction of error to previous post on Brehna series (must be getting old) :

There are sixteen notes, not twelve. And the towns on them are : 1. Brehna 2. Bitterfeld 3. Clöden (now Klöden on the Elbe) 4. Elster 5. Herzberg 6. Jessen 7. Kemberg 8.Löbnitz 9. Lochau (now going by the name of Annaburg since the 16th century in fact; not be confused with the Lochau near Leipzig) 10. Muldenstein 11. Brettin 12. Pouch (pronounced roughly similar to the English word “poke“) 13. Schlieben 14. Schweinitz 15. Wettin and 16. Löben.

Sorry for any confusion. And sorry, Tony, if you’ve already set off on an epic journey to find these places with the previous dodgy information …

I guess either i terribly misidentified the note, or we finally found a note I need to paste.

Here is the 25pf note:

Ello,

Today we look at Bruchhausen. Specifically, Series 190.1, 01 Mk, Schloss Bruchhausen, 01 May 1921. Here the front image is a bit dramatic. If I am to believe my translation of the front image, we are looking at the ‘Holy Woman of Bruchhausen’. The words translated, yet the scene does not. This does not seem a scene of great respect. What am I missing?

Thanks,

Jack

Hi Jack,

The Brehna 25-Pfennig pieces all have the coat of arms of the ancient County of Brehna (here in the archaic spelling : Brene), three red hearts inset with trefoils on a silver field, placed back-to-back with the arms of Saxony. They all read Grafschaft Brene umfaßte (“[The] County of Brehna encompassed”) and each note has a different town or village. Number 3 is Clöden [on the Elbe]; nowadays it’s spelled as Klöden. The other towns and villages are : 1. Brehna 2. Bitterfeld 4. Elster 5. Herzberg 6. Jessen 7. Kemberg 8.Löbnitz 9. Lochau 10. Muldenstein 11. Brettin 12. Löben.

Hope this helps!

John,

Thank you for all your help with Braunschweig, that town of beer and bread.

Today we address the town of Brehna.

Series 160.2:

25 Pfg, Bild 3 Lloden, townscape, July 1921

Umfasste: 3. Löden

(translated 13 September 2020)

Included: 3. Löden

<<???>>

Thanks, Jack

Hi Jack,

the other statues you intended to ask after are :

25 Pfennig : Duke Henry the Lion and his wife Matilda of England (again); here the likenesses are taken not from the old town hall (as on the 50-Pfennig note) but from their tomb in the cathedral.

75 Pfennig : the figures are from the facade of the town St Andrew’s Church, and represent the Holy Family on the Flight into Egypt, with St Joseph on the left and the Madonna and Christ Child on a donkey on the right. When I went to Brunswick the church was covered in scaffolding, but fortunately the scaffolding itself was then helpfully covered with a hoarding showing the figures hidden behind it.

Hi Jack,

the translation of Awer de Deigapen backet noch immer! is in the third paragraph of my reply under 155.1 25 Pfennig Eulenspiegel as a baker; the German text is in the second line, as the final clause of the rendering of the German in italics; the English translation (“But those pastry monkeys are still baked today!”) is at the end of the third line and runs into the fourth. I didn’t think I’d missed anyhting, but I appreciate that there was a lot of text in my post.

To see a picture of the traditional pastry owls and apes which are still baked in Brunswick today, go to : https://www.braunschweig.de/tourismus/ueber-braunschweig/spezielles/spezi_apen.php.

I feel that my trip to Brunswick to sample the beer may now involve a sampling of their pastries … not that I need an excuse …

Best wishes as always,

John

Sorry, could not find a way to edit my prev post:

The statues I referred too where not on a single bulding, but to the statues in the panels of the 25, 50 and 75 pfg notes

thanks

John, great as usual.

I guess you were already drinking to the memory, as you missed at least one phrase.

Amer de Deigapen backet nach immer!

(translated 30 August 2017)

Amer de Deigapen bakes after ever!

<<???>>>

Super info John – much appreciated!!

Hi Jack,

Gotta love the Braunschweig notes! The Eulenspiegel series was one of the first that I collected, and has a special place in my heart; I spent a pleasant day in the town a few years ago, looking out the different locations and statues on the Alt-Braunschweig set, and chatting to the nice people in the town museum who were very helpful. And 158.1 has one of my fave playwrights, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, so let’s see what we can do to help.

155.1, 10 Pfennig :

“Ulenspeigel is nich mid Schanne / von enem Essel uteschetten / in Knettlingen in usem Lanne / hat Heilebort en in de Weege smetten / Hei was en dönschen Kerl vull Strike / un kam in Mölln tor Erd as Like” (Eulenspiegel was not shamefully shat out by a donkey; / in our very own Kneitlingen he was thrown into the cradle by the stork, / He was a foolish fellow full of tricks / and his body was buried in Mölln).

155.1, 25 Pfennig (Eulenspiegel as a baker):

“Statts Lussen dä hei Apen maken / un Ulen un Krein un annere Saken / Blot Pennige kosten sei dortaumalen / Nu most du mer dafor betalen / denn de Tiden sind slimmer / Awer de Deigapen backet noch immer!” (Instead of loaves he made monkeys / and owls and crows and other things. / They used to cost just pennies, / though now you have to pay more for them / for times are harder. / But those pastry monkeys are still baked today!)

155.1, 50 Pfennig (Eulenspiegel as a lover) :

“Füer Leiw un Brannewien / de slimmsten Fiend vom Kassenschien. / Doch kannst ohn Sluck un Damp nich sin. / Säuck dick dat schönste Öwel ut / Un nimm ne lüttje säute Brut” (A warm fire, love and strong drink / are the enemies of the pocketbook. / But you can’t live without drink or food / So find yourself the finest vice / and take a sweet young thing as your bride).

155.1, 75 Pfennig (Eulenspiegel as a doctor) :

“Nist daun, Slapen, freten, supen, Sachte gahn un pupen Dat sleit an” (Do nothing, sleep, scoff, sup, / walk but slowly and break wind. That’s the trick).

155.2, 10 Pfennig :

BRUNSEWYK DU LEIWE STADT / VOR VEL DUSENT STÄDEN / DEI SAU SCHÖNE MUMME HAT DAR IKK WORST KANN FRETEN (Brunswick you dear town / Ahead of many thousand others / Which has such lovely Mumme beer / Where I can eat sausage)

155.2, 25 Pfennig :

MUMME SMEKKT NOG MAL SAU FIN / AS TOKAY UN MOSLER WIN / SLAKKWORST FÜLLT DEN MAGEN / MUMME SETTET NEYRENTALG (Mumme beer tastes much finer / Than Tokay or Moselle wine / Salami fills the stomach / Mumme builds up kidney fat)

155.2, 50 Pfennig :

WENN IKK GNURRE KYVE BRUMM / SLEPE MIKK MIT SORGEN / EY SO GEET MI GUDE MUMM / BET TAUN LECHTEN MORGEN (When I growl or moan or grumble / Or drag my heels in sorrow / O give me good Mumme beer / Until the last day dawns)

[You asked about the pictures. The note shows the Altstadtmarkt, the Old Town Market Square, with (l. to r.) St Martin’s church, the market fountain and the old town hall, upon the façade of which are 17 figures of the town’s rulers. These include the statues of Duke Henry the Lion and Duchess Matilda, as shown here, as well as three emperors, one king and four further dukes along with their wives.]

155.2, 75 Pfennig :

MUMME UN EIN STÜMPEL WORST / KANN DEN HUNGER UN DEN DORST / OK DE VENUSGRILLEN / OGENBLIKKLICH STILLEN! (Mumme beer and a sausage sliced / Can still hunger and thirst / And even lovesickness / In but a moment!)

158.1, obverse of all notes :

Geld-zetul / ausgegangen bey währender nothzeyt / darinnen all gut geld durch den erschröcklichen krieg ist verschlungen. – Nimbt in diessem 1921 jar für beygesatzten ehrlichen gelds-werth an / des gemeynen volcks bibliotheka und lese-stuben / auff deme Gewandhause / in der stad zu braunschweich (Money notes / are run out in the current time of distress / wherein all good money has been devoured through the terrible war. – Take in this year 1921 for the value of honest money so replaced / of the common people’s library and reading rooms upon the clothing house / in the town of Brunswicke)

[NB a pseudo-medieval text decrying the financial distress of the post-war period and requesting that the notes be accepted as legal tender. All very tongue-in-cheek] ]

158.1, 10 Pfennig :

O, was ist die deutsch Sprak für ein arm Sprak! für ein plump Sprak! (Oh what a poor language is the German language! What an awkward language!).

[NB from Lessing’s play Minna von Barnhelm, in broken German, as spoken by the character the Chevalier Riccaut de la Marlinière, Seigneur de Pret-au-val, a pompous French mercenary in Prussian service]

Hope that this is helpful and informative. Apart from the pseudo-medieval German and the deliberately broken German, most of the above is in local Eastphalian dialect. Regrettably I didn’t try the Mumme beer when I was there, so I feel another visit coming on!

Greetings,

This time we look at Braunschweig, specifically the Eulenspiegal and Alt Braunschweig series. Again, I believe these are common enough to be in most collections. So I will not burn up space hosting them images.

First we will list series 155.1:

10 pfg, Eulenspeigal with Owl, 01 May 1921:

Eulenspiegel is nict mid Schanne von enem Essel uteschetten in Kneitlingen in usem Lanne hat Heilebort en in de Weege smetten Hel was en donschen Kerl null Strike an Aam in Molln tor Er as Lisse

(translated 03 September 2020)

Eulenspiegel is not in the middle of a donkey uteschetten in Kneitlingen in us Lanne has Heilebort en in de Weege smetten Hel was en donschen guy null Strike an Aam in Molln tor Er as Lisse

25 pfg, Eulenspeigal with Monkey, 01 May 1921:

Ulenspeigel as Backer

Statts Luffen dä hei Apen maken un Ulen un Kreln un annere Saken Blot Pennige kosten sei dortaumalen. Nu most du mer dufor betalen denn de Fiden sind glimmer.

(translated 30 August 2017)

Ulenspiegel, as in the case of the Apes, and the Kremn and the Saken Blot. Nu most you mer dufor betalen because de Fiden are glimmer.

<<???>>

Amer de Deigapen backet nach immer!

(translated 30 August 2017)

Amer de Deigapen bakes after ever!

<<???>>>

50 pfg Eulenspeigal Als Liebhaber, 01 May 1921:

Feur Leiw un Branne Wein de slimmsten Fiend vom Kassenschien doch kannst ohn Sluck und Damp nich sin Sauck schonste Owel ut Un nimm ne luttie saute Brut!

(translated 03 September 2020)

Feur Leiw un Branne Wein the worst enemy of the cash register but you can not without sluck and steam are suck suck owel Ut Take no luttie saute brut!

<<????>>

75 pfg, Eulenspiegal als Arzt, 01 May 1921

Nist daun slapen freten supen sachte gahn un pupen dat sleit an

(translated 03 September 2020)

Nest daun, slap, fry supen, gently gahn and dolls on it

<<????>>

Series 155.2:

10 pfg, town view, ‘Appelhans’, 01 May 1921:

Brunsewyk du Leiwe Stadt vor vel dusent Staden die sau schone mumme hat dar ikk worst kann freten

(translated 04 September 2020)

Brunsewyk du Leiwe City in front of vel dusent Staden the sau schone mumme has dar ikk worst can fret

<<????>>

10 pfg, town view, ‘no printer name’, 01 May 1921

Brunsewyk du Leiwe Stadt vor vel dusent Staden die sau schone mumme hat dar ikk worst kann freten

(translated 04 September 2020)

Brunsewyk du Leiwe City in front of vel dusent Staden the sau schone mumme has dar ikk worst can fret

<<????>>

25 pfg, alt burgplatz, ‘Vieweg’, 01 May 1921:

Mumme Smekki Nog Mal Sau Fin As Tokay un Mosler Wynslakkorst Füllt den Magen Mumme Set Tet Neyrent Alg

(translated 22 August 2017)

Mumme Smekki Nog Mal Sau Fin As Tokay un Mosler Wynslakkorst Fills the stomach Mum Tet Tet Neyrent Alg

<<????>>

25 pfg, alt burgplatz, ‘Appelhans’, 01 May 1921:

Mumme Smekki Nog Mal Sau Fin As Tokay un Mosler Wynslakkorst Füllt den Magen Mumme Set Tet Neyrent Alg

(translated 22 August 2017)

Mumme Smekki Nog Mal Sau Fin As Tokay un Mosler Wynslakkorst Fills the stomach Mum Tet Tet Neyrent Alg

<<????>>

50 pfg, alt stadtmakt, Appelhans’, 01 May 1921:

Fy so geet mi gude mumm

Wenn ikk gnurre kyve brumm

Slepe mikk mit sorgen

Bei iaun lechten morgen

(translated 04 September 2020)

Fy so geet mi gude mumm

When ikk gnurre kyve hum

Slepe mikk with worries

At iaun lechen tomorrow

<<???>>

Thoughts on the front image:

>>>statue one?

>>>fountain in old marketplatz?

>>>statue two?

75 pfg, wollmarkt, ‘no printer listed’, 01 May 1921

Mumme un ein stumpel worst kann den hunger un der dorst ok de venusgrillen ogenblikklich stillen!

(translated 04 September 2020)

Mumme and a stump worst can satisfy the hunger in the Dorst ok de venusgrillen ogenblikklich!

<<???>>

Series 158.1a:

10 pfg, Gotthold Lessing, 1921

O, roas ist die deutsch Sprak für ein arm Sprak! Fur ein plump Sprak!

(Minna von Barnholm)

(translated 10 September, 2020)

O, roas is the German language for a poor language! For a clumsy tongue!

(Minna von Barnholm)

<<???>>

Geld zetus Ausgängen ben mährender notchzent darinnen all gut Geld durch den erschrofflichen Krieg ist verschlungen. Nimbt im diessem 1921 tar fur bengesatzten ehrlichen geldswerth an des gemennen volcks bibliotheka und lese-stuben auff deme Gemandhause in der stad zu Braunschweich

(translated 10 September 2020)

Money zetus exits beneath a morose notchcent all good money from the terrible war is swallowed up. In this 1921 tariff for bengesatzten honest monetary value to the common people library and reading rooms on the Gemandhaus in the city of Braunschweig

<<???>>

25 pfg, Louis Spohr, 1921:

Geld zetus Ausgängen ben mährender notchzent darinnen all gut Geld durch den erschrofflichen Krieg ist verschlungen. Nimbt im diessem 1921 tar fur bengesatzten ehrlichen geldswerth an des gemennen volcks bibliotheka und lese-stuben auff deme Gemandhause in der stad zu Braunschweich

(translated 10 September 2020)

Money zetus exits beneath a morose notchcent all good money from the terrible war is swallowed up. In this 1921 tariff for bengesatzten honest monetary value to the common people library and reading rooms on the Gemandhaus in the city of Braunschweig

<<???>>

50 pfg, Franzt Abt, 1921:

Geld zetus Ausgängen ben mährender notchzent darinnen all gut Geld durch den erschrofflichen Krieg ist verschlungen. Nimbt im diessem 1921 tar fur bengesatzten ehrlichen geldswerth an des gemennen volcks bibliotheka und lese-stuben auff deme Gemandhause in der stad zu Braunschweich

(translated 10 September 2020)

Money zetus exits beneath a morose notchcent all good money from the terrible war is swallowed up. In this 1921 tariff for bengesatzten honest monetary value to the common people library and reading rooms on the Gemandhaus in the city of Braunschweig

<<???>>

75 pfg, William Raabe, 1921

Geld zetul ausgangen ben währender nothzent darinnen all gut geld durch den erschröfflichen krieg ist verschlvngen. Nimbt in diessem 1921 jar für ben gesatzten ehrsichen geldswerth an des gemeynen volcfs biblotheka und lese – stuben auff deme Gewandhause in der stad zu braunschweich.

(translated 03 September, 2017)

Money zetul exhausted nothzent in it all good money through the frröfföfflicher war is verschnng. Nimbt in this 1921 jar for ben gesatzten honorable worth at the common volume biblotheka and reading – rooms on the Gewandhaus in the stad zu braunschweich.

<<???>>

Thanks again for all thought s and efforts,

Jack

John, that was helpful to us all. thanks.

teehee…..

Oops my Bad (see what I did there?)

Hello –

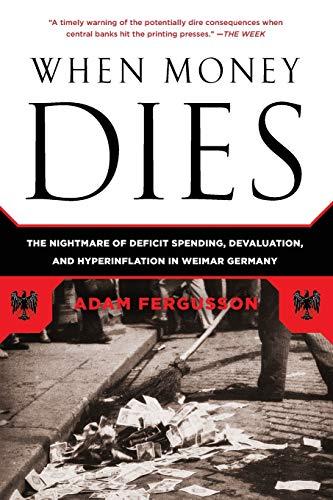

I thought that I would recommend a book I just read called When Money Dies by Adam Fergusson. This book deals with the 1919-1924 German Post WWI Hyperinflation and touches on Austria and Hungary as well.

While it talks about notgeld, this book is NOT a notgeld book. Rather, it is an inciteful work that talks about some of the harsh realities of the era and a lot of the reasons for it. I’ll admit, some of it is dry, especially when dealing with the pure financial aspects of governmental administrative actions, but overall I found it to be quite interesting and a worthwhile read, giving a small glimpse into the era and its impact that notgeld was a necessary part of.

Hi John – I’m in Germany trying to find Bad Bramstedt from your descriptions…….

Small correction to previous post! I got my Bramstedts mixed up!

Bad Bramstedt, the issuer of the notes, is not in the District of Cuxhaven as stated but rather in the District of Segeberg in Holstein, a bit further north. There is a different Bramstedt in the District of Cuxhaven, but not one that is likely to be renowned for its Roland statue or its spa waters and mudbath cures.

Apologies to both Bramstedts and anyone in the forum confused by my error which I am happy to correct. I hope that no one has gone to to the wrong Bramstedt in the last week and been disappointed on the basis of my claims :).

Hi Jack,

Interesting that the search results claim the text to be in Luxembourgish, which is a Germanic language very close to German. It is in fact in one of the several versions of Low German, in all probability the version known as Hadler Platt, spoken in and around the District of Cuxhaven where Bad Bramstedt is located.

The obverse of the 25-Pfennig note shows the town’s statue (dating back to 1693) of the hero Roland, a commonplace fountain or marketplace motif in Northern and Central Germany and beyond, as an assertion of municipal rights and freedoms (there’s a great book on these statues by Dietlinde Munzel-Everling, entitled Rolande). The text reads :

Uns‘ Roland steiht un kiekt un nöckt.

He seggt: „De Welt, de is verrückt.

Ick mag hier nich mehr länger stahn,

Ick will man leewer rünnergahn.

Ick gah nah Bielenbarg nu aff,

Dar legg ik mi ganz still int Graff

Un slaap dar, bet in Kopp un Hart

De Minschheit wer‘ vernünftig ward.“Our Roland stands and looks and teases,

He says : “The world is crazy.

I don’t want to stand up here anymore,

I rather want to get down.

I’m going to set off to Bielenberg,

And I’ll lie down quietly in a grave

And have a sleep there, while I pray with head and heart

That humanity will be brought to reason.”

The statue makes another appearance on the reverse of the 50-Pfennig note, which shows the locals about to perform their tradtional dance around the statue, or rather its wooden predecessor (c. 1533-1694) :

De Bramstedter Buern danzt an’n drütten Pingsdag 1674 üm den Roland, weil se ehr Freeheit kregen harrn. — Düt ward hüt to Dog noch mackt.

The Bramstedt farmers dance around the Roland on the third day of the season of Pentecost in 1674, because they got their freedom. – This is still done to this day.

The accompanying verse is presumably sung while the dance is performed :

Solang de Wind weiht

Un de Hahn kreiht,

Schall um’n Roland danzt warrn

Wenn de Sünn ünnergeiht!As long as the wind blows

And the cockerel crows

Around the Roland we shall dance

As the sun goes down!

The Roland statue makes a third appearance on the front of the 50-Pfennig note, in the town’s coat of arms. Here the verse details its validity, terms and conditions :

Düß Schien, de gelt sien föfti Penn.

Doch eenmal hett dat ock en Enn.

Denn kannst du lesen in uns‘ Blatt:

,De Schiens sünd all nu vör de Katt!“

Denn bring em gau hen nah de Kass‘,

Du büß sünst an de Kossen faß.This note is worth its fifty pfennigs.

But that will one day come to an end.

You can read about it in our newspaper :

“The Notgeld notes are all worthless now!”

So bring them to the finance office,

Otherwise you’ll be responsible for the cost.

The expression for worthlessness / pointlessness / a waste of time is in German “for the cat”, from the 16th-century fairy story “The Blacksmith and the Cat.” Here, instead of standard High German für die Katz’, we have the dialect version vör de Katt.

The reverse of the 25-Pfennig note has, instead of the town’s Roland statue, a picture of its mineral water spring and a dubious four-verse paean to the same :

Hest du all mal von Bramstedt hört?

Und von sien brunes Water?

All mennig een hett dat kureert,

Keen Water is probater.Wenn se hierher kamt ut de Stadt,

Denn könnt se knapp noch krupen,

Se sünd nervös un sonst noch wat

Un hebbt den Kopp voll Rupen.Denn plümpert se hier jeden Dag

In uns‘ oll dreckig Water.

Slank ward se as en Bohnenschach

Un bruner as en Tater.Un ook de Rupen in den Kopp

De speelt nie mehr Theater.

De ganze Minsch, de leewt wer‘ op,

Blot von dat brune Water.Have you ever heard of Bramstedt?

And of its brownish water?

It’s cured all kinds of people,

No water is more effective.

When they came here to the town.

They could barely even crawl,

Their nerves are bad and they’ve other woes

And their heads are full of buzzing.

And then they splash here every day

In our old dirty water,

They become as slim as a beanpole

And browner than a Tartar.

And all the buzzing in their heads

No longer gives them bother.

The whole person is brought to health,

Just from the brownish water.

The verses were written by the local dialect poet A. Kühl. As usual I’ve been a little free with translation sometimes, in order to render meaning better; for example, I’ve translated Rupen in den Kopp as “buzzing in the head”, where the original actually has “caterpillars in the head”.

Hope this helps and is of interest to forum fans!

Greetings,

Today we address Bad Bramstedt. Series 151.1,

Weirdly, the computer claims a fair amount of the text is in Luxembourgish.

Series 151.1

25 pfg, Fountain, 07 Dec 1920

Writing on the front:

<poem>

Heft du mal von Bramstedt hört?

Un von sien brunes Mater?

All menning een hett dat fureert,

Keen Mater is probater.

Menn fe hierher kam ut de Stadt,

Denn konnt se fnapp noch frupen,

Se fund nervös un fonst noch wat

Un hebbt den Kopp voll Rupen

Denn plumpert se hier jeden Dag

In uns all dreckig Mater

Slank warrd fe as en Bohnenschach

Un brunner es en Tater

Un oct de Rupen in den Kopp

De speelt nie mehr Theater

De ganze Minsch, de leemt mer‘ op,

Blut von dat brune Water

Have you ever heard of Bramstedt?

And from his brown mate?

Every opinion has a fury,

No Mater is probater.

Men came here from the city,

Because she could barely speak,

She feels nervous and finds something else

Un raises his head full of scars

Because they plump here every day

In us all dirty mater

Slim warrd fe as en Bohnenschach

Un brunner es en Tater

Un oct de Rupen in den Kopp

He never plays theater again

The whole Man, the ‘me’,

Blood from that brown water

<<???>>

<< poem by A. Kühl>>

Writing on the back:

Uns Roland steiht un fieft und nockt.

He seggt: De Welt de es verrückt.

Ick mag hier nich mehr langer stahn ,

Ick will man leewer runnergahn.

Ick gah nah Beilenbarg nu aff,

Dar lagg ick mi ganz still int Graff

Un slaap bar, bet in Kopp un hart

Die Min schheit ner ‘bernunftig ward.“

>another quote by A. Kuhl<

Uns Roland stands up five and nudges.

He says: The world that drives it crazy.

Ick may not stand here any longer,

Ick want man leewer runnergahn.

Ick gah nah Beilenbarg nu aff,

Dar lag ick mi ganz still int Graff

Un sleep bar, bet in Kopp un hart

The mine is not “childish”.

>another quote by A. Kühl <

<<???>>

<><><><><><><>

50 pfg, Pentecost 1674, 07 Dec 1920

Writing on the front:

Solang de Wind weiht

Un de Hahn kreiht

Schall um’n Roland danzt warrn

Wenn de Sünn ünnergeiht!

As long as the wind blows

And the rooster crows

Sound around Roland dances were

When the sun goes down!

<<???>>

De Bramstedter Buern danzt an’n drutten Pingsdag 1674 um den Roland, weil se ehr Freeheit kregen harrn. – Düt ward hüt to Dog nach mackt

The peasants of Bramstedt danced around Roland on the third day of Pentecost 1674, because they were given their freedom. – Düt ward hüt to Dog nach mackt

<<???>>

Writing on the back:

Notgeld von de holsteensche Stadt Bad Bramstedt

Emergency money from the Holsteenian City of Bad Bramstedt

<thinking Holstein is Germanic region>

Dütz Schein, de gelt sien föfti Penn.

Doch eenmal hett dat ock en Enn,

denn kannst du lesen in uns Blatt:

„De Schiens sünd all nu vör de Katt!“

Denn bring em gau hen kah de Kass,

Du bütz fünft an den Kossen fasz.

Dütz Schein, de gelt sien föfti Penn.

But once it has ock and Enn,

because you can read in our sheet:

“De Schiens sins now in front of the cat!”

Denn bring em gau hen kah de Kass,

You beat five on the pillows.

>>???<<

Thank you again,

Jack

Hi Jack,

You’re very welcome!

Your translation of the caption is pretty much there : Wie man in Brakel früher die Diebe bestrafte can be rendered as “How we used to punish thieves in Brakel” (or “How they used to punish thieves in Brakel” or “How thieves used to be punished in Brakel”, using the passive voice; the literal translation is “How one used to punish thieves in Brakel” but that’s a linguistic formulation in English that seems only to be popular with King Charles these days).

Best wishes as always,

John

Thanks John.

Seems I missed a question though. Hopefully I did not miss any more.

Wie man in Brakel

Früher die Diebe

Bestrafte!

(translated 08 January 2015)

How to Brakel

Previously, the thieves

Punished!

<<???>>

Then again, the more I stare at this, the more more i wonder if this was meant be transcribed as a single line. If so, with a few a couple grammatical changes, do I have translation already?

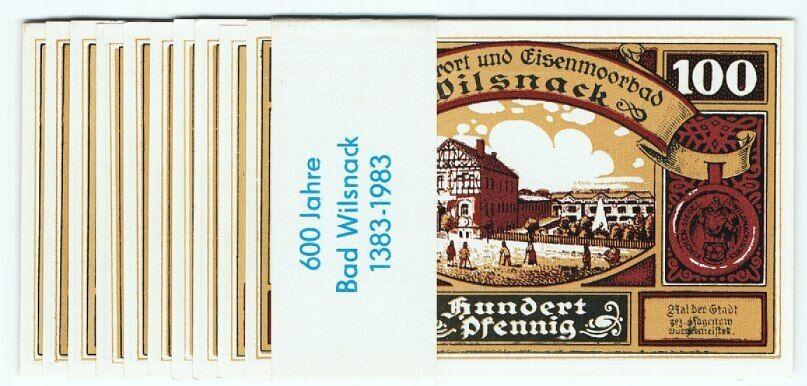

WILSNACK

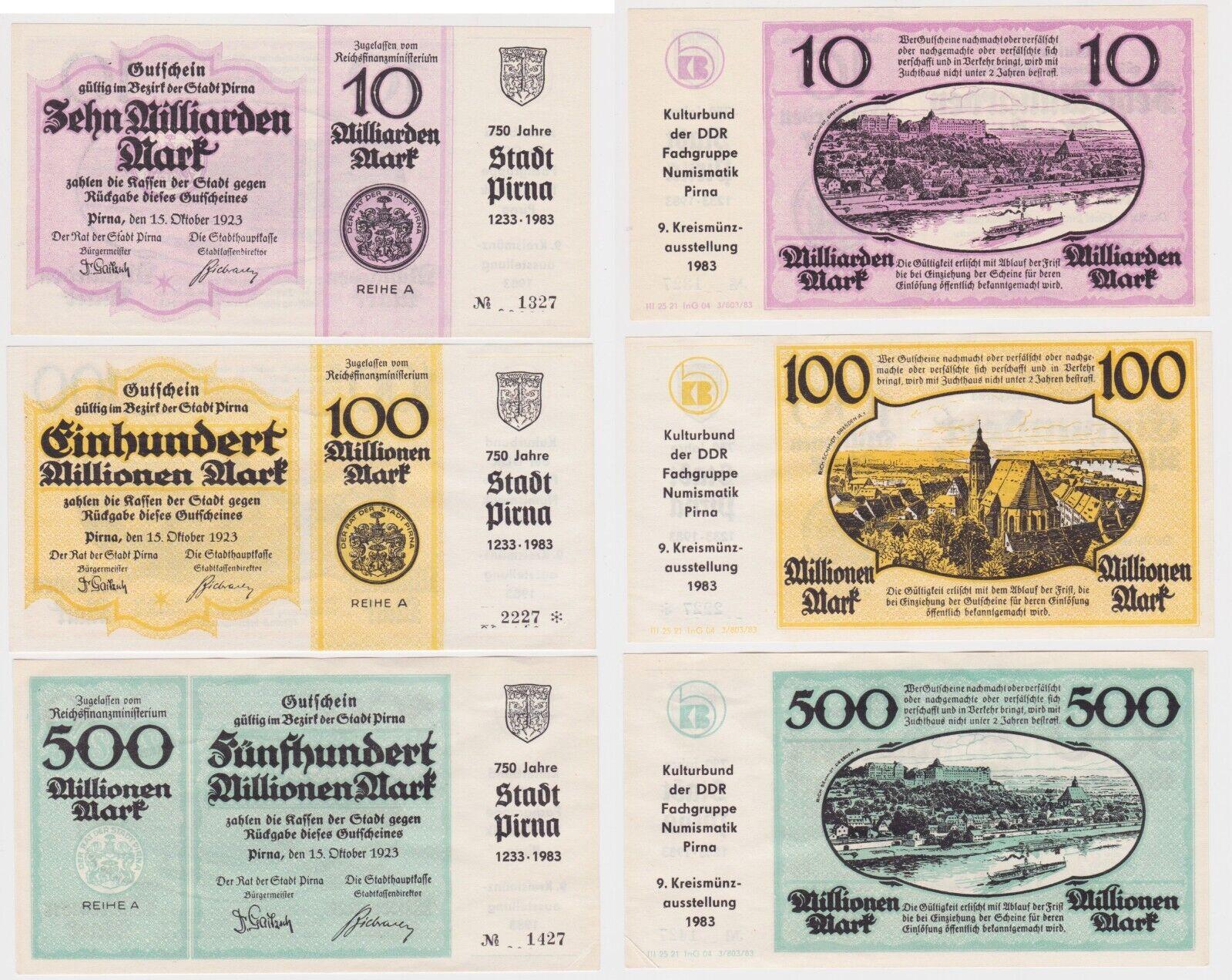

The wrapper keeps the complete serie (12 x 50 Pf) of the reprinted Serienscheine of 1921 with a new date of issue (1983). It is a souvenir of the 600 years city jubilee in 1983. (See the catalog below)

(picture: Internet)

Hi Jack, many thanks for your kind words! Although I wasn’t quite around in the 1920s, I do travel around Germany a bit and have been a bit of a Germanophile for over 40 years, and as I’ve been collecting Notgeld for nearly 20 years my passions seem to coalesce.

The Brakel set is often regarded as anti-Semitic but I think a more nuanced interpretation would see that only one note – although that’s bad enough – is actually anti-Semitic, the 2-Mark note with the Jewish man chained to a pillory on the obverse. It seems that because of this people often think that other pictures in the series must be anti-Semitic too.

The victims of brutal forms of justice on the back of the 50-pfennig note are not noticeably stereotypically Jewish, nor identified as such. The theme is captioned as “How we used to punish thieves in Brakel” (Wie man in Brakel früher die Diebe bestrafte), and the malefactors being ducked and caned are “black marketeers, usurers and wastrels”. Obviously, there is the old libelous trope of Jews being automatically synonymous with usury since the Middle Ages (often the only business which they were legally allowed to engage in outside the ghettos). But the victim of medieval dunking has neither the cartoon stereotypical features of a Jew (as does the figure in the pillory), nor is he wearing any clothing identifying him as such i.e. the gabardine coat of the pilloried Jew, or a conical or pointed hat, or a Star of David. I imagine that die-hard anti-Semites would have been triggered by the word usurer, but otherwise it’s a bit of a thin connection.

Here’s the original and a translation :

Solche Wippe, stark von Eisen, / Taucht man kurzer Hand ins Wasser. / Auch für heute wär sie praktisch / Für die Schieber, Wucherer, Prasser.

Was der Einfalt nur erscheinet / Als ein Instrument zum Sitzen, Dieses wußten kluge Richter / Pädagogisch auszunützen.

Such a ducking stool, made of strong iron, / Is ducked into the water in peremptory manner. / It would also be practical today / For black marketeers, usurers and wastrels.

What might seem to a simple mind / An instrument on which to sit, / This the clever judges of yore / Knew how to use to teach a lesson.

The 1-Mark note with the image of St Anne’s Chapel on the obverse has a story about the chapel on the back, the story of Dat Mäken von Brakel (The Maiden of Brakel), taken from the Kinder und Hausmärchen (Children’s Fairy Tales and Fairy Tales for the Home) by the Brothers Grimm (1840) :

Et gien mal ’n Mäken von Brakel na de Sünt Unnen Kappellen uner de Hinnenborg, un weil et gierne ’n Mann heven wulte un ock meinde, et ware süs neimes in de Kappellen, sau sank et „O hilge Sünte Unne, help mie doch bald tom Manne. Du kennst ’n ja wull : He wuhnt vor’m Suttmerdore, hed gele Hore :Du kenns ’n ja wull.“ De Köster stand awerst hünner de Altare un höre dat, da rep he mit ’ner ganz schrögerigen Stimme : „Du kriggst ’n nig, du kriggst ’n nig.“ Da Mäken awerst meinde, dat Marienkinneken, dat bie de Mudder Anne steiht, hedde üm dat to ropen, da war et beuse un reip : „Pepperlepep, dumme Blae, halt de Schnuten un lat de Möhme kühren (die Mutter reden).“

[The bit in brackets at the end is the translation by the Brothers Grimm of the final phrase, which is so far removed from standard German ( the whole story is in Westphalian dialect) as to be otherwise unintelligible to outsiders.]

In English : Once upon a time a maiden of Brakel was passing by the Chapel of Saint Anne beneath Hinnenburg Castle, and because she wanted dearly a husband and thought that there was no no one else in the chapel, she sang : “O holy Saint Anne, help me to get a man. You know him well : he lives down by the Suttmer Gate, and has blond hair : you know him well.” The verger however was standing behind the altar and heard that, whereupon he called out in a most croaky voice : “You’ll not have him, you’ll not have him.” The girl thought however that the Child Mary, who stood next to Mother Anne, had called out to her, so she was angry and called back : “Stuff and nonsense, silly child, shut your face and let mother do the talking.”

We can see in the picture the face of the naughty verger peeping out, red-nosed, from behind the altar of St Anne, depicting the grandmother of Christ and her child Mary the Mother of Christ, and calling to the pious girl who has even taken off her clogs as a gesture of respect before kneeling before the altar.

The reverse side of the 2-Mark note tells a rather more earthy story :

Ne beste Kamer harr’ wi nit, / Dorüm dat Jüngsten ut dat Finster schitt. / Jedoch – o weh – en Unglück gafst dorbi : / En Ratsmann gung akkrat vorbi, / De hätt dat Traktamente krumm genomen / Un is sin an den Kaak gekuomen.

Wahrhaftige Geschichte anno 1655

We don’t have a lavatory, / So the youngest would shit out of the window. / But – oh woe – that was when an accident happened : / One of the town councillors was passing directly by, / And he took the entire allowance in the wrong way / And ended up in the cack.

True story from the year 1655

The word Traktamente stands in here for Exkremente, a s ahumorous bowdlerisation or malapropism. Traktament was a word of Swedish origin (swathes of Northern Germany were overrun by the Swedes in the Thirty Years’ Way, including Brakel in 1646), it meant a financial allowance; I’ve tried to keep that sense in the translation.

A final word on the anti-Semitic cartoon on the front of the 2-Mark note; in the issue catalogued G / M 150.1, the figure has exaggerated and stereotypical “Jewish” facial features, which were a staple of e.g. early 20th-century anti-Semitic postcards and later National Socialist publications such as Der Stürmer. It may actually have been so offensive that it seems to have been softened on the later re-issues of the series, 150.2 and 150.3, where we see that buildings have been added and the outline of the figure’s face has been turned to be slightly less obvious. Lindman notes in his catalogue, where the three series are numbered 142a, 142b and 142c : Bei b. und c. ist das Bild des 2-Mk-Scheines verändert (“With b and c, the picture of the 2-Mark note has been changed”).

Greetings,

Today we now review series 150.3 and 150.1

The series of this town are again listed as anti semitic. I am pretty sure these notes tell a story as well. Given the theme, a troubling or insulting story would not surprise me.

Golche Wippe, stark von Eisen,

Taucht man kruger hand ins Wasser

Auch für heute wär sie praktisch

Für die Schieber, Wucherer, Prasser!

(translated 08 January 2015)

Golche rocker, hard of iron,

If you dive kruger hand into the water

Even today they would be practically

For the slide, usurers, gluttons!

<<???>>

Was der Einfalt nur erscheinet

Als ein Instrument zum Citzen

Dieses wußten kluge Richter

Bädagogisch auszunützen.

(translated 08 January 2015)

What the simplicity only appeareth

As an instrument for Citzen

This did wise judge

Bädagogisch exploit.

<<???>>

Wie man in Brakel

Früher die Diebe

Bestrafte!

(translated 08 January 2015)

How to Brakel

Previously, the thieves

Punished!

<<???>>

Die Maken von Brakel.

(translated 26 August 2020)

The Maken of Brakel.

<<???>>

Et gien mal ‘n Maken von Brakel na de fünf Annen Kapellen uner de Hinnenborg, un weil et gierne ’n Mann heoen wulle un ork meinde, et wäre sus neimes in de Kapellen, sau sank et „O hilge sunte Anne, help mie doch bald tom Manne. Du kennst ‘n ja wull.“ De Hoster stand awerst hunner de Altare un hore dat, da rep he mit ‘ner gans schrogerigen Stimme: „Du kriggst ‘n nig, Du kriggst ‘n nig.“ Dat Maken awest meinde dat Marienkinnneken, dat bei derMudder Anne steiht hedde dat um to ropen, de war et beuse un reip: „Pepperlepep dumme Blae, halt de Schnuten un lat de Mohme kuhren (die Mutter reden).“

(translated 26 August 2020)

There was a maken from Brakel to the five Annen chapels under Hinnenborg, and because et gierne ‘n man heoen wulle un ork meinde, et would be sus neimes in the chapels, sau sank et “O hilge sunte Anne, help me soon tom Manne. You know ‘n ja wull. “De hoster stood awerst hunner de Altare un hore dat, da rep he with a goose scruffy voice:” You krigg’ n nig, you krigg ‘n nig. “Dat Maken awest meinde dat Marienkinnneken, dat with the Mudder Anne, hedde dat to ropen, de war et beuse un reip: “Pepperlepep stupid Blae, halt de Schnuten un lat de Mohme kuhren (the mother talk).”

<<???>>

Ne beste kamer harr’ wi nit.

Dorüm dat Jüngsken ut dat finstrer schitt.

Jedoch-o weh-en Unglück gafst’dorbi:

En Ratsmanngung akfrat vorbi,

De hätt dat traktamente frum genuomen:

Un if sin an den Raaf gekuomen.

(translated 08 January 2015)

Ne best kamer harr ‘wi nit.

Dorüm dat dat Jüngsken ut gloomy schitt.

But-alas-en misfortune gafst’dorbi:

En councilor Gung akfrat vorbi,

De’d dat traktamente frum genuomen:

Un sin if gekuomen to the Rav.

<<???>>

Once again I have to hope there can be more to these notes than hatred against Jews. Though I accept the hatred of Jews had for the longest time to wide a public acceptance, I cannot help but hope that there is some redeemability to the message of these notes. That hatred is not all there is.

Jack

Thanks John,

excluding some of the more evil subjects, I would almost accept as given that you were a) around to invent German notgeld, and b) spent enough time wandering German history taking notes on subject matter on the nearest convenient surface.

You seem that aware of notgeld.

:)

Jacks

Thanks John – the piece has been posted to you.

Hi Jack,

the Bordelum notes are partly in High German and partly in Nordergoesharder Friesisch, one of the ten surviving North Frisian dialects. Fif-en-söbenti Pen. is, in High German : Fünfundsiebzig Pf. (75 pfennigs). Pen. or P are abbrevaiations of the Frisian word Penning, where Pf. or Pfg. or common abbrevaitaions of the High German Pfennig.

The motto Lewwer düad üs Slaav! (“Rather dead than a slave!”) is on a large number of notes from the Prussian province of Schleswig-Holstein (with a lot of variant dialect spellings). It is connected to the tradition of the Friesische Freiheit, Frisian Freedom, the claim sunk in the mists of time that the peoples of Frisia were granted freedom of all lordship save that of the Emperor alone, as a reward for their warriors’ bravery in imperial service. Frisian and Low German variants of the motto gained currency in Northern Frisia during the 1840s and in the aftermath of the Great War, particularly before, during and after the plebiscites of 1920 which decided the post-war fate of Northern Schleswig. There is a classical pedigree to the phrase, in Cicero’s mors mihi est servitude potior.

Hope this helps! Best wishes as always.

Greetings,

Now we look at Bordelum, series 143.

Fif en sobenti Pen.

(translated 22 August 2020)

Fif en sobenti Pen.

<<???>>Lewwer düad üs slaav!

(translated 22 August 2020)

Lewwer düad üs slaav!

<<???>>

Possibly a regional dialect??

thanks for all help.

Jack

Thanks,

It was helpful and incredibly informative.

It is sad situation that symbol that was respectable so long over so much of the world is now tainted. Though Hindus and some other faiths still are able to see the original meaning in the swastika, the Nazi’s have ruined it for a greater portion of the planet.

What once meant ‘sun’ or ‘good fortune’. now represents some of worst fortunes of the twentieth century.

Will submit the next one soon.

Jack

Hi Jack,

The verses on the reverse of the notes seem to come from three sources.

The ones on the Wohldenberg hunting note (25 Pf. #1), the Bodensteiner Klippen note (50 Pf. #2) and the castle ruins note (75 Pf. #1) seem to be by a local poet (going by the references to the Ambergau, which is very small and not renowned in German literature) and strike a pseudo-Romantic note.

The ones on the church note (25 Pf. #2), the townscape note (50 Pf. #1) and the dean’s house note (50 Pf. # 3) are anti-Semitic and seem to derive from a far-right nationalist source, perhaps a newspaper , periodical or flyer; putting them together is interesting as the metre is similar and they may well be the work of one author. NB the “dwarven horde”, with its baleful power of gold to corrupt the warriors, is likely racialist code for Jews corrupting Aryans; the word Aryan itself is from an Indo-European root meaning “warrior”.

I think that the verse on the Merian engraving note (75 Pf. #3) likely belongs to this latter group, with its dark mumblings about German tribal lands and the phobic eye-rolling about the worm gnawing on the (German) oak and weakening it for destruction in the next storm.

I can identify the verses on the 1-Mark notes exactly. The notes are devoted to the humorist and poet Wilhelm Busch (1832-1908) : one has his portrait and one has his grave at Mechtshausen near Bockenem (Grabstätte Wilhelm Buschs in Mechtshausen bei Bockenem). The obverse of the first has two quotations from his works, from Die Fromme Helene (Pious Helene), one of his anti-clerical satires, the other from Julchen (Little Julia), the third work of his Knopp Trilogy. The second note has in its entirety the poem Mein Lebenslauf (The Course My Life Has Run), written on the occasion of his 75th – and final – birthday.

You’ve inspired me to dig a little deeper in my researches and I found a reference in an old newspaper with some interesting news!

It seems that Herr Rehmann, the anti-semitic National Socialist publisher of the notes, attracted the notice of the authorities with his propaganda. The Social Democrat Newspaper Die Volksstimme (The People’s Voice), based in Magdeburg, reported on Saturday 19th August under the headline “German Nationalist Notgeld” : Recently we have been informed that in a town in Hannover Notgeld has been circulated to the values of 25, 50 and 75 Pfennigs, which not only feature the swastika but also show verses, such as : The free German man became a serf, / The Jew counterfeits German law /And passes it on to his heirs. As the Swabian Daily Sentinel (Schwäbische Tagwacht) reports, even in Württemberg propaganda has been made with these Notgeld notes, which is indicated by the discovery of an entire bundle of such notes in a forest near Stuttgart. On this paper money it is written that : “This note can can be redeemed in my premises until 31. 12. 1923. Heinr. Rehmann, Book Printing, Bockenem.” As the official “Prussian Press Agency” has heard from the appropriate authorities, a criminal charge has been made against the publisher of these Notgeld notes, Herr Rehmann in Bockenem, by the State Prosecutor in Hildesheim.

What I find interesting here – apart from Herr Rehmann getting his come-uppance – is that the notes were clearly being used in a far-right propaganda campaign to spread the perverted gospel of anti-Semitism across the Republic, over a year before the Nazis’ attempted coup in Munich in November 1923. A whole bundle of them found in a forest in far-away Swabia seems to indicate the widespread intended covert use of Notgeld as a political tool.

Hope that this helps to answer your question, and adds a bit of extra interest for frequenters of the forum.

Very best wishes in your job search. I hope that you find something fitting and fulfilling very soon.

Greetings John,

Rather helpful you are.

As I am under employed and job searching, I find myself with quite a lot of notgeld time. This might distract me a bit from the depressing situation.

On the last set, only question thus far… are all the verses on the various notes part of a single literary work?

Jack

Hi Tony, what a lovely note. It would probably be classed as a Spendenschein as it give thanks for the Spende (donation) of 5 Kronen to assist the work of Perchtoldsdorf’s Healthcare at Home organisation (Hauskrankenpflege).

It seems to show Christ at the healing / restoring to life of Jairus’ daughter, and the verse is entirely Christian in tone and content.